Everywhere one turns around the United Nations, the word ”stakeholder” seems to have displaced ”non-governmental organizations”, ”civil society organizations”, ”constituencies”, ”communities”, and even ”citizens”. More recently the UN Secretary-General advocated in an influential report called ”Our Common Agenda” that the future of multilateralism should strongly rely on multistakeholderism. His language even sometimes merges multistakeholderism and multilateralism together into what he calls ”UN 2.0”. This should raise alarm as the concept has serious democratic limitations.

Origins in gambling and the business world

The origin of the stakeholder as a term of art is from the world of gambling. Two people bet on an outcome and, as neither fully trusts the other, they hand over their stakes in the gamble to a ”stakeholder”. Subsequently the term was coopted into management speak. Corporate advisors were telling boards of directors and executives that they should broaden their horizons from ”shareholders” to encompass stockowners, workers and customers which they called in aggregate corporate ”stakeholders”. This approach was moved to the broader economic frame by the World Economic Forum which in 2005 introduced the concept of ”stakeholder capitalism”.

Neither stakeholder nor multi-stakeholder governance are compatible with democracy

In none of these contexts, democracy plays a central role.

In fact, neither ”stakeholder” governance nor ”multistakeholder” governance are compatible with democracy. In what we shall call multistakeholderism or Msism in short, one or more of the founding members of a given stakeholder group select the key members, one or more of which are from the corporate community. ”Stakeholder” governance thus is an introductory linguistic step toward legitimating ”multistakeholder” governance without any central role for democratic representation.

Proponents of multistakeholderism do present a number of claims about its democratic nature. They say that it brings into decision-making more than governments because governments are not really representative of the public; it provides a formal seat at the table for different ”stakeholders” granting them a role in governing a particular topic; it builds upon the idea of ”public-private partnerships” where all levels of government, community organizations and corporations are said to work together well at delivering public services. What is side stepped by these claims is that the participants are self-selected and hand-picked. Further, corporate stakeholders usually have a disproportionate power inside a multistakeholder group from the very beginning.

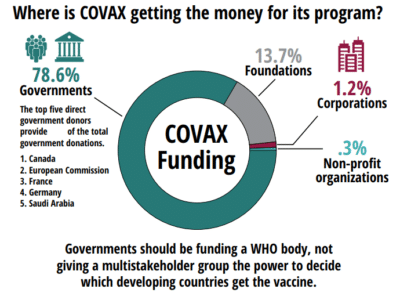

The UN’s commitment to multistakeholderism

The UN Secretary-General’s office has been expanding its commitment to MSism as a component of multilateralism since at least 2019. That year his office signed a contentious Memorandum of Understanding with the World Economic Forum which outlines joint coordination on MSism between the UN’s Secretariat and the business group in Davos. The current UN Secretary-General has also called for funding the multistakeholder COVAX organization rather than the WHO directly to manage the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in the Global South and advised governments in ”Our Common Agenda” report that they should support the creation of six new multistakeholder groups to handle cutting-edge global issues while pointedly calling for no new intergovernmental treaty negotiations on pressing international topics.

The normalization of the stakeholder language and approach is becoming pervasive in other parts of the UN system as well. The co-facilitators appointed by the UN General Assembly’s President to help prepare the upcoming UN summit on the Sustainable Development Goals and the UN’s Summit of the Future recently hosted so-called ”stakeholder consultations”; the leading civil society coalition that is preparing input for the Summit of the Future, the Coalition for the UN We Need, uses the stakeholder term regularly in their communications; the UN’s High Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development co-sponsors annually a Stakeholders-Partnership Day.

This spring the UN Secretary-General provided a briefing to delegates on the state of play of the OCA process using, I believe, for the first time the phrase ”non-governmental stakeholders” in an official context. The Secretary-General also stated clearly that the UN Secretariat would not be making any proposals to revise the UN Charter. But the Secretary-General is doing this in practice regarding the role of civil society and non-governmental organizations at the UN.

Amending the UN Charter ”by practice”

The UN Charter, adopted in 1945, names the five veto members of the Security Council including The Republic of China (Taiwan) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). As times have changed, these two seats became held by the Russian Federation and the Peoples Republic of China. This type of change to the Charter, known in UN parlance as ”amending the Charter by practice”, goes on regularly. It operates by recognizing political realities when there are no longer strenuous objections.

In the Charter, there is a whole section on how ”non-governmental organizations” can bring their knowledge and expertise to the UN’s Economic and Social Council. Over the years the groups named ”non-governmental organizations” have striven to shift the public vocabulary to reflect the positive contributions that they make. Indeed many UN resolutions in the past decades have used the terms ”civil society organizations” or ”major groups” to welcome their participation. The UN Secretary-General’s language is facilitating a de facto change to the UN Charter language when he introduces the new term ”non-governmental stakeholders”, an expression closer to the political views of the World Economic Forum than the Charter.

Fortunately, governments in the UN General Assembly are still called ”member states”, not ”state-stakeholders” and the UN Charter still opens with ”We the Peoples”, not ”We the Stakeholders”.

A narrowing scope of civil society participation

The effort to normalize ”stakeholder” language in international relations is going on in parallel with attempts to narrow the scope of civil society participation in global governance. Civil society organizations are not one homogenous category. In global debates, it is important for example to give separate space to the scientific community, to local community groups, to social movements, to workers, to gender-based communities, to geographically-based groups; and to the private sector. All of these ”legal entities”, ”constituencies”, communities”, ”non-governmental organizations” and ”citizen bodies” should be able to address directly intergovernmental bodies and the UN Secretariat.

However, the international business world has a different view about inclusiveness for multistakeholder bodies. In the climate area, for example, they are arguing that there should be separate seats for investment banks, financial advisors, venture capitalists, pension consultants, manufacturers, retail firms, international accountants, and others in the financial and service industry, some seats for willing governments and a seat for civil society, portraying civil society as on single body.

This application of the ”stakeholder” approach to multiple types of corporate firms, which claim they have a ”stake” in an issue, highlights the democratic limitation of the concept. In the case of multistakeholder groups in the food arena, there are probably over eight billion people who have a more legitimate ”stake” in the rules of the food market than any given agribusiness corporation. Yet the international advocates of ”stakeholder” governance are proposing that they can legitimately designate ”representatives” of all these people who are faced with varying degree of malnutrition and a diversity cultural food practices in governing arrangements.

Push back

It is encouraging that on the same day when the UN Secretary-General introduced his new ”non-governmental stakeholder” vocabulary a significant number of governments, particularly from the Global South, in their floor statements rejected this direction. Nonetheless, some of this rejection comes from self-interested commitment by delegates to protect ”national sovereignty” and some comes as a disguised way of restricting too much non-state involvement in intergovernmental meetings.

It is also encouraging that a growing number of civil society organizations and constituencies are clearly saying multistakeholderism and corporate engagement in global governance is not the way forward. One sees this perspective in the critiques of COVAX, in the battle to contain the follow up to the Rome Food System Summit and in broad civil society demands in the Financing for Development process. There is also now an international coordination mechanism in civil society, the People’s Working Group on Multistakeholderism which is talking of a “corporate takeover of multilateral institutions” and provides a platform for sharing counter-strategies.

When given the opportunity, it is far better to return to calling non-state participants by one of more clearly democratic terms, like citizen groups, peoples, communities, or constituencies and avoid legitimating multistakeholderims via the use of ”stakeholder” language.