The 2022 edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index that was published earlier this month reports overall democratic stagnation in a year marked by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and a lack of democratic revival following COVID-19-related lockdowns and restrictions.

The state of national democracy worldwide

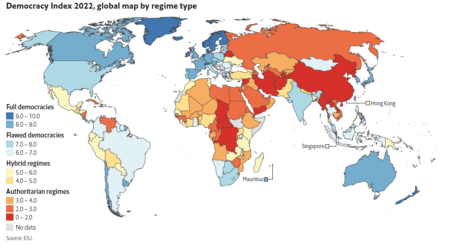

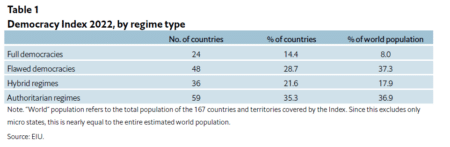

According to the 2022 Democracy Index 8% of the world’s population in 24 countries live in a full democracy, 37.3% in 48 countries in a flawed democracy, 17.9% in 36 countries in a hybrid regime, and 36.9% in 59 countries in an authoritarian regime. The global average score in 2022 was 5.29 which is slightly better than the score of 5.28 in 2021. After years of continuous regression since at least 2015 (with a score of 5.55), democratic development in 2022 seems to have reached a point of stagnation. Stagnation seems better than regression, but according to the report, it should be considered a disappointment “given expectations that there might be a rebound in the overall index score as pandemic-related prohibitions were lifted over the course of the year.”

In the 2022 assessment, there are only five changes of regime category compared to the previous report, three positive and two negative. Chile, France and Spain returned to the “full democracy” category while Papua New Guinea and Peru moved from a “flawed democracy” classification to that of a “hybrid regime”.

How the report measures democracy

EIU’s Democracy Index has been published annually since 2006. It makes an assessment of the state of democracy in 165 independent states and two territories, only microstates are excluded. Each country receives a score on a scale from 0-10 based on a range of indicators within five categories: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government, political participation; and political culture. Based on the average score the measured countries end up in one of four categories: “full democracies” (with a score of 8+ to 10); “flawed democracies” (6+ to 8); “hybrid regimes” (4+ to 6); and “authoritarian regimes” (0 to 4). The level of democracy in organizations of transnational governance, such as the European Union or the United Nations, is not covered.

Best performers and developments

From a regional perspective, Western Europe experienced the most significant democratic improvement, going from the all-time low during EIU’s coverage of 8.22 in 2021 to 8.36. Among the 14 full democracies in Western Europe, the Nordic countries stand out as in previous years. With a score well above 9 they hold five of the top six positions. Norway keeps the top position with 9.81, New Zealand registered as second with 9.61, Iceland (9.52), Sweden (9.39), Finland (9.29) and Denmark (9.28), following behind.

From a country perspective, Thailand experienced the single best improvement, with an increase by 0.63 points from 6.04 in 2021 to 6.67 in 2022. Angola, Greece, Montenegro and Niger were also registered as good performers. Greece, which is still categorized as a flawed democracy, is close to taking the step to a full democracy.

Russia and Ukraine

There was also democratic decline in many countries. The report highlights that China’s low score continued to decline and the worst performer was Russia. From an already low rate of 3.24 in 2021, Russia’s score dropped by 0.96 down to 2.28. Its global ranking fell from 124th to 146th, bringing it close to the bottom. According to an analysis in the report, this dramatic decline is related to Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine, which has led to an “increase in state repression against all forms of dissent and a further personalisation of power, pushing Russia towards outright dictatorship.”.

In a special essay, democratic development in Ukraine and the failure of democracy in Russia is discussed. So far Ukraine had its peak as a flawed democracy in the years after the “Orange revolution” in 2004, the report says, with a high score of 6.94 in the Democracy Index of 2006-2008, and then again declining into a hybrid regime after that. Following the Maidan protests in 2014, there seems to have been steady improvements, however disturbed by the COVID-19 pandemic and threatened by Russia’s invasion and the war. The essay emphasizes the interdependence between national sovereignty and democracy and concludes that “Russia’s war of aggression has raised the level of national consciousness and will amplify expectations of change afterwards.”