“The Bretton Woods institutions,” said Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados, at this year’s UN General Debate, “no longer serve the purpose in the 21st century that they served in the 20th century.” And in fact, in the crisis-ridden years of the early 21st century, key institutions of the UN system are unable to effectively support those most in need.

During the pandemic, vaccines reached the poorest too late – if they did so at all. Multilateral financial support and debt relief was too little to avert the mounting debt crises in low- and middle-income countries. At the same time, the worsening hunger crises are forcing an underfunded World Food Programme to “take from the hungry to feed the starving.” The UN’s office for humanitarian affairs reports “the biggest funding gap we’ve ever seen, mostly because the number of vulnerable people who need support is increasing fast.”

But does it have to be this way? Why can’t global institutions provide much-needed help to those in need? What reforms are needed?

The IMF and the World Bank need to be reformed

Closing the funding gap for the UN’s humanitarian operations is a start. But it will remain a band-aid unless reforms target the institutions of the UN system with the largest financial firepower: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

With a maximum lending capacity of 1 trillion dollars, the IMF acts as the world’s lender of last resort for countries without access to capital. In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the IMF gave out loans worth more than 100 billion US dollars. Its sister organization, the World Bank, is the world’s largest development bank. Each year it spends around 50 billion US dollars on development projects in areas such as infrastructure, education, and health.

Together, the two institutions thus control ample global resources. But do they reach those who need them most? Not always. A series of studies have shown that economic need is only one of the factors that influence how the IMF and the World Bank distribute their money. Countries considered more influential politically and more relevant geopolitically often receive more and larger loans. For instance, countries that are elected to the UN Security Council and thereby gain political weight receive more money from these institutions for the two years of their membership; and if they vote in line with the US government, this further increases inflows. Countries that vote with rich countries in the UN General Assembly also receive more money from the two institutions.

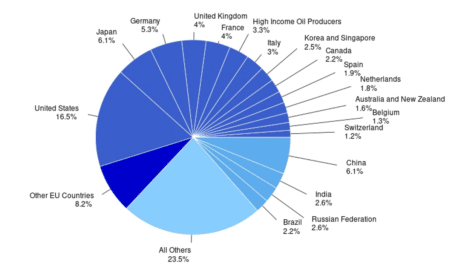

How come? Both the IMF and the World Bank have a peculiar governance structure. They are controlled by boards where voting power depends on the economic size of their member states. The formula according to which this is calculated gives the US government a vote share of 16 percent – effectively a veto power in important decisions that require 85 percent of votes. As large European economies also have substantial voting power, a small number of rich countries can easily organize majorities. An informal agreement ensures that the World Bank is always led by a US-American and the IMF by a European. Both organizations are headquartered in the US capital and employ many economists from high-income countries. All this skews formal and informal influence over these organizations in favor of rich states.

Poorer states lack influence

Poorer states lack such influence. A country like Ethiopia – home to more than 100 million people – controls only 0.09 percent of the votes in the IMF. In general, most low-income countries do not even have their own seats on the boards. Instead, they share their seat with country groups. Several academic studies show that this institutional arrangement weakens countries without a seat at the table. Countries with seats get more money.

Considering how political power is distributed within these organizations, their policy priorities should come as no surprise. IMF conditions typically focus on debt repayment to investors, cuts to public expenditures and economic liberalization. The burden of economic adjustment is thus often carried by the poor – and IMF interventions, on average, lead to rising inequalities. By contrast, policy initiatives that would benefit the poor have a hard time in these institutions. Proposals to get rid of IMF surcharges for highly indebted countries were recently rejected – as were proposals to direct more of the IMF’s new resources to low-income countries. Instead, the IMF’s recent liquidity boost was, again, proportional to economic size and benefited the richest countries the most. All African countries combined received less than Germany alone.

Multilateral policies for the global poor are unlikely to succeed as long as multilateral resources are controlled by the global rich. What can be done to change that?

Reforming the distribution of voting power

A variety of reforms could restrict the informal influence of high-income members: abolishing the gentlemen’s agreement that allows only US-Americans and Europeans to head these institutions and increasing the competitiveness of how senior staff are selected. It seems absurd that then-President Trump could single-handedly select the current World Bank President and expect him to ensure the bank’s activities “serve American interests and defend American values.”

More fundamental reforms would target the political boards of these institutions – the place where decisions on allocating resources are made. As long as political influence on these boards only derives from economic strength, it is unlikely that they would serve the economically weak.

Enhancing the legitimacy of multilateral financial institutions also is in the interest of their major shareholders. Otherwise, the global financial architecture will continue its process of fragmentation and states will increasingly turn to bilateral lenders.

But what are the alternatives to the current structure? One vote for each country, as in the UN General Assembly? Such a system gives disproportional weight to smaller states. In fact, the evidence on development aid suggests that small states like Tuvalu, Nauru and Palau receive most bilateral support per capita not least because their governments’ votes in the General Assembly are cheap to buy. Plus, a system that gives greater power to the few thousand inhabitants of such microstates than to more than two billion Indians and Chinese will hardly be defensible for an institution that distributes so many resources.

A compromise could be to combine the existing system with elements of a one-country-one-vote system and with the principle of proportionality to population. Voting power could be distributed by assigning a third of the votes each according to financial contributions, population size and equality across governments. As a first step, such a redistribution of voting power could even be achieved by maintaining the current structure of the institutions’ executive boards.

Citizen representation beyond governments

Nonetheless, citizen representation eventually needs to go beyond governments and include parliaments – both in the IMF and the World Bank as well as in the UN system as a whole. This would enhance the access of marginalized and vulnerable groups to the global politics of allocating multilateral resources. It would also facilitate transnational political alliances that could rally behind joint reform proposals.

Whether such representation of citizens can be organized through the Inter-Parliamentary Union, assemblies of national parliamentarians, or a directly elected UN parliament, as suggested by Democracy Without Borders and the “We The Peoples” campaign, is up for debate. What is important for the global poor is that the multilateral financial institutions are included when citizen representation in the UN system is strengthened. Those whose needs for multilateral resources are greatest would then no longer be the ones whose voices are heard the least. As former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali pointed out when the campaign for a UN Parliamentary Assembly was launched, the new assembly should “become a force to provide democratic oversight over the World Bank, the IMF and the WTO.”